Tech Articles

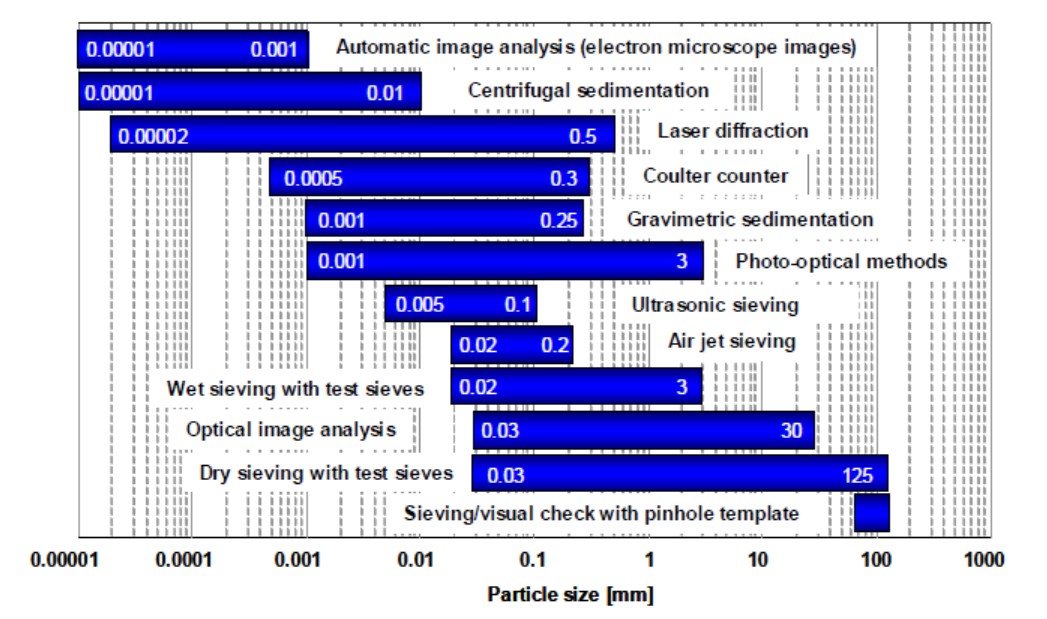

There is a wide range of measurement methods for particle sizing, each of which has capability over a certain range of particle size. Figure 1 provides a guide to the particle size ranges that are said to be measurable by each technique. For particles greater than about 50 μm in diameter, the simplest method is probably sieving. This in effect provides a go/nogo test for particle size. For particles less than 100 μm, the focus of this Guide, usually indirect measurement methods are employed.

The principal methods that have been studied are the following:

Laser diffraction

Sedimentation of a suspension

Electrozone sensing

Other techniques are feasible, such image analysis, but these have not been examined in detail.

Since Laser Diffraction was the technique of choice for the vast majority of industrial companies taking part in Round Robin work, findings and recommendations inevitably and unavoidably lean towards this technique. However, users of other techniques should find plenty of useful prompts.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the particle size ranges in which each sizing method is thought to be capable of operating

1. Laser diffraction

The principles of laser diffraction for particle sizing are comprehensively summarised in the international standard ISO/DIS 13320 and the NIST Recommended Practice Guide. Laser light incident on a particle is diffracted by interaction with the particle surface, producing a pattern of light intensity which can be captured by multi-element detectors around the beam and particle. All other parameters being constant, the pattern is characteristic of the particle size and, using either the Mie or Fraunhofer theories, deconvolution of the pattern yields a volumetric particle size distribution.

The general assumption in laser diffraction is that particles are spherical; calculations within the software work out an equivalent sphere based on particle volume. Particles that deviate from a sphere such as needles and platelets (chalk, clays and crystalline materials) produce a reduction in the accuracy of the reported sizes (a single size might in fact be considered insufficient to describe such particles accurately). This is due to the 2-dimensional features of the platelets and needles. For instance the following figure demonstrates the range of shapes for calcium carbonate. The calculations will not be accurate either if light is scattered by more than one particle, so there is a clear requirement that the concentration of particles passing through the system is controlled below a certain limit.

Both theories can be applied to particles larger than the laser light wavelength, but only the Mie theory can be applied to particles smaller than this limit. It relies on knowing both the real and imaginary parts of the particle’s refractive index, which, while generally well defined and documented for the real component of most materials is much harder to obtain/determine for the imaginary component as it depends on the shape and surface roughness of the particles. Using different values for the imaginary refractive index can, for example, produce a 50% variation in the d10 value for a silica powder with a d50 of approximately 1 μm. The Fraunhofer theory, while only applicable to particles > 1-2 μm does not require knowledge of the particle optical properties, and can therefore be particularly useful for mixed or unknown powders.

One of the key differences in design between different instruments is the number and positioning around the laser/particle interaction volume of the detectors that collect the scattered light signal. These differences and the resulting differences in algorithms used to relate the detector signals to the theoretical diffraction patterns can account for some of the variability when different instruments are used to measure the same powder sample.

2. Sedimentation methods

Sedimentation methods for determining particle size are based on Stokes' Law, which defines the velocity of particles settling in a viscous liquid under the influence of an accelerating force such as gravity. Sedimentation techniques can be cumulative or incremental. In the cumulative method, the rate at which particles settle is determined, whilst in the incremental method the change in concentration or density of the material with time is measured at known depths. For the latter, optical or X-ray sensing is typically employed. Sedimentation methods are best suited to particles in the range 2-50 μm. Limitations of the technique include the fact Stokes Law is only valid for spheres and particles unaffected by Brownian motion (the latter limiting sub-micron particle measurement). For very large particles, using a higher viscosity liquid to suspend particles can be employed to extend the upper size limit. It is important to know the density of the powder under investigation and to have reasonable temperature control to avoid fluctuations in the viscosity of the liquid phase.

In practice a powder sample to be measured is suspended homogeneously in a fluid, and a horizontally-collimated beam of X-rays employed to directly measure the relative mass concentration of particles in a liquid medium. The method is useful for wide size distributions, but is sensitive to shape and density variations within single samples. Each mass measurement represents the cumulative mass fraction of the remaining fine particles. Particle size may also be determined from velocity measurements by applying Stokes law under the known conditions of liquid density and viscosity and particle density. Settling velocity is determined at each relative mass measurement from knowledge of the distance the X-ray beam is from the top of the sample cell and the time at which the mass measurement was taken.

Increasingly, there is interest in Disc Centrifuge Sedimentation techniques. The general principle involves use of a polymer disc with internal space (to accommodate the sample) rotating at any speed up to 24,000rpm. A suspension injected at the centre of the spinning disc is spun out, such that particles separate according to size. Towards the perimeter of the disc, particles pass through a blue light with turbidity measurements used to determine concentration. This technique is very useful for sub-micron size particles where settling times in conventional apparatus would be excessive.

3. Electrozone sensing

Electrozone sensing equipment (also known as Coulter counters) analyse powder particles maintained as a dilute suspension in an electrolyte. Two electrodes in the suspension are separated by a very small aperture and by applying a field between the two electrodes, the particles are induced to flow through the aperture, producing a voltage pulse. The size of the pulse is proportional to the particle volume, enabling a distribution of particle size assuming equivalent spheres to be obtained from the number and size of pulses.

The size of the aperture needs to be selected to suit the particle size and the counting rate. If too large an aperture is chosen then the risk of multiple particles passing through it together and being counted as a single particle increase. The dilution of the powder sample must also be maintained below a level that avoids multiple particle counting. The method avoids the

need to know physical properties of the powder being analysed and is suited to low particle concentrations. The limitations of the aperture result in a lower size limit of about 0.4 μm and clearly very wide size distributions will be more difficult to measure.

All Rights Reserved by Gold APP Instruments Corp. Ltd.

WeChat WhatsApp

GOLD APP INSTRUMENTS CORP. LTD.

HongKong Add: Flat Rm A17, Legend Tower, No. 7 Shing Yip Street, HK, China

Mainland Add: R1302, Baoli Tianyue, Shaowen Rd., Yanta Dist., Xi'an 710077, China

T: +86-182 0108 5158

E: sales@goldapp.com.cn